This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

CMU Trends Labels & Publishers Legal

Trends: Copyright changes

By Chris Cooke | Published on Wednesday 15 January 2014

Copyrights got longer this year, though exemptions are set to expand too, and while there was lots of talk of simplifying licensing, things remain rather complex for now.

COPYRIGHT EXTENSION

The sound recording copyright term extended to 70 years across Europe this last year. The European Directive enabling the change was actually issued in 2011, but the law was only updated on 1 Nov 2013. It means any recording released in 1963 now has another 20 years protection in Europe. Something key for the UK record industry because The Beatles and all the lucrative British rock n roll of the 1960s properly got going that year (though ‘Love Me Do’ was released in 1962 and went public domain last January).

It’s worth noting that while the copyright for released recordings has extended to 70 years, the copyright in unreleased records still only lasts for 50 years, from the date of recording.

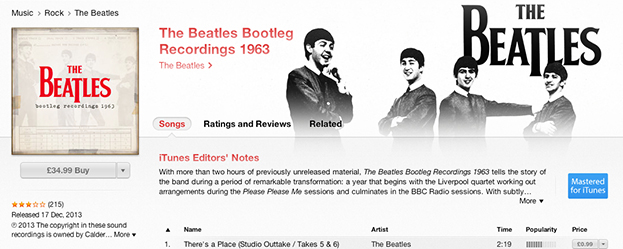

Which means any unreleased master-recordings gathering dust in a cupboard need to be made public within 50 years to ensure the 70 year term, and indeed those releases would then get 70 more years of protection, because the release, providing it occurs within the first five decades, reboots the copyright. Universal and Apple Corps led the way in this domain by releasing a whole stack of previously unheard 1963 Beatles recordings in December, ensuring the reboot.

Now the extension has occurred, it will be interesting to see what impact, if any, the accompanying ‘use it or lose it’ clause may have. Because political leaders were persuaded of the need to extend the sound recording copyright term based on the benefits to musicians rather than labels, a number of artist-friendly measures were also introduced. This includes giving musicians, including featured artists and session musicians, the power to take copyright works off labels which fail to distribute them (digitally and physically), so that the artists can exploit their economic rights. It remains to be seen if any artists exercise this power (it only kicks in at 50 years), and how the labels respond – ie will it motivate them to unlock deleted catalogue?

FAIR USE EXTENSIONS

While political decision makers may have extended the copyright term enjoyed by the record industry, elsewhere the reaches of copyright are being constrained in the UK through the extension of what might be called ‘fair use’ provisions in other jurisdictions (though technically speaking not this one).

That is to say scenarios in which users can legitimately make use of copyright material without license. The negative impact of these extensions are minimal compared to the positive impact of the record industry’s term extension, and many of the new fair use exemptions already exist in the US and elsewhere in Europe, though that hasn’t stopped some in the music rights sector expressing concern at these developments.

The extension of what might be called ‘user-rights’ in the British copyright system was proposed in the 2011 Hargreaves Review of intellectual property law, and in 2013 the IP Office published various documents explaining how each new user-right might work, then seeking stakeholder input. Content companies tend to be suspicious of any expansion of user-rights, and have therefore been quietly lobbying against all these moves.

For the music industry the two new user-rights of interest are the ‘parody’ and so called ‘format shifting’ – or ‘private copy’ – rights. The former says that creators can adapt another creator’s work without licence if they do so in order to parody the original, while the latter says that any consumer can make private back-up copies of recordings they purchase, for example ripping tracks from a CD to PC.

Regarding the latter proposal, no one in the music industry objects in principle to the introduction of a private copy right. After all, while technically it’s currently infringement if you rip a CD to a PC for private use, everybody does it, and no rights owner would ever sue someone who makes private back-ups. And the private copy right exists in most other jurisdictions, while the UK government’s 2006 Gowers Review of IP, as well as the aforementioned Hargreaves Review, have both said it should be introduced here.

However, elsewhere in Europe, the private-copy right is accompanied by a levy, traditionally applied to blank cassettes and CDs, and more recently to digitial music players, that is paid back to the music community as compensation for the legitimised user-copying. But Hargreaves proposed a private copy right without levy, and it’s that point that the British music industry is lobbying against.

The strongest argument for the levy in the UK is parity with the rest of Europe; and indeed, as the music business on the Continent fights to keep its levy as it gets harder to choose a device to attach it too (as smartphones replace MP3 players as primary music devices), perhaps the British music rights sector has a duty to fight the fight here too. Though in the wider scheme of things it’s a nominal income, and you can’t help thinking that the music industry at large would gain more by showing it can be flexible on copyright when common sense says it should be.

But expect this debate to rumble on as the IPO moves to make the new fair user exemptions law in the coming year.

SIMPLER LICENSING

And talking of common sense in IP, the other area of copyright politics getting some attention in 2013 was the simplification of licensing. Whenever political leaders give a little to the copyright lobby these days – whether term extensions or some new anti-piracy flim flam – a quid pro quo often demanded is that copyright owners make it easier for people to license their content. It’s actually a simple thing for the music rights business to commit to, given “we need to simplify licensing” is a common mantra at the sector’s own conferences, though delivering on that commitment is another matter.

This year a Copyright Hub website was launched, backed by the content industries though mainly funded by government, which in theory will help licensees through the licensing process. Though it currently feels very much like a work in progress.

Meanwhile, the music publishing sector continued work on its copyright-owner-logging Global Repertoire Database, announcing the opening of offices in London and Berlin to manage the project. Though it’s still some way off actual launch, and still seemingly has the flaw of only mapping song and not recording copyrights.

And as for collective licensing, the UK’s two music rights societies, PPL for the labels and PRS for the publishers, launched a handful of new joint licenses, so that licensees can clear song and recording copyrights in one go, though such licenses still only apply in a very small number of scenarios.

All steps in the right direction of course, but pretty small steps to date. And from village halls wanting to play some records to media firms promoting new music to digital start-ups trying to secure a catalogue of content, most licensees still moan relentlessly about the music industry’s licensing processes.

Of course some of those moaners are just pissed off that they have to pay copyright owners anything to use their content, but others do have a point that navigating the licensing journey can be tortuous, even when rights owners are keen to license. Let’s just conclude: much work still to be done.